In the humid summer air across North America, a formidable aerial predator cuts through the atmosphere with the precision of a military aircraft. The Black Horse Fly (Tabanus atratus) represents one of nature’s most impressive—and intimidating—flying insects, commanding respect from both wildlife enthusiasts and unsuspecting hikers alike. These robust flies have perfected the art of blood-feeding over millions of years, becoming some of the most efficient hunters in the insect world.

Identification and Appearance

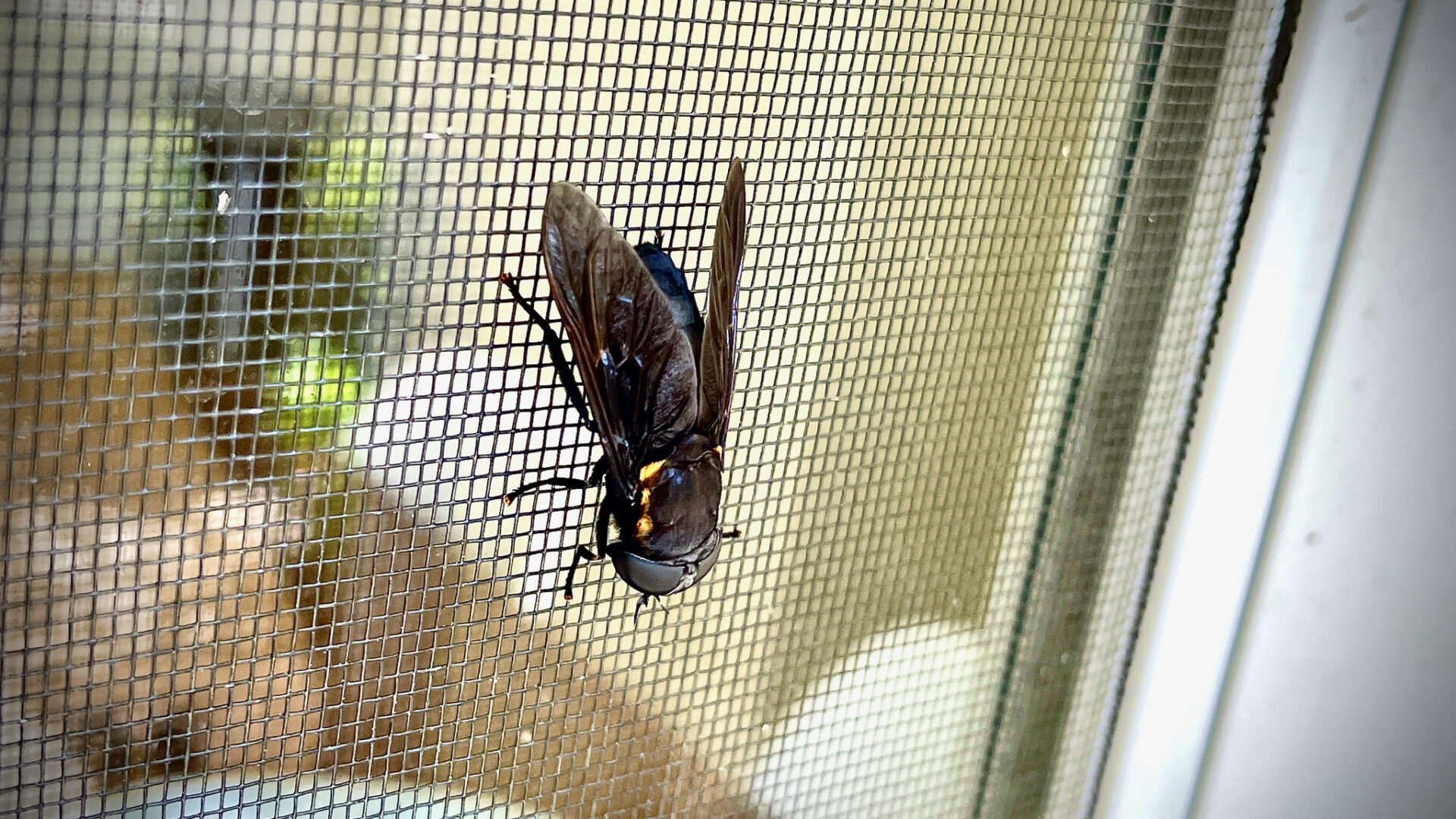

The Black Horse Fly lives up to its common name with a striking, predominantly black appearance that makes it unmistakable in the field. These substantial insects measure between 20-25 millimeters in length, making them among the largest flies in North America. Their robust, muscular bodies gleam with a metallic sheen that shifts from deep black to dark bronze depending on the angle of sunlight.

Perhaps most remarkable are their enormous compound eyes, which can occupy nearly half of their head. These iridescent orbs shimmer with bands of green, gold, and purple, creating a mesmerizing kaleidoscope effect that serves a deadly purpose—detecting the slightest movement from potential hosts. The eyes are particularly prominent in males, who use their enhanced vision for territorial displays and mate-seeking flights.

Their powerful wings span nearly 40 millimeters when fully extended, producing the characteristic loud buzzing sound that announces their presence from considerable distances. The wings appear clear with subtle smoky tinting, supported by prominent dark veins that create intricate patterns. Sexual dimorphism is evident in the eye structure: males possess larger, more closely-set eyes that nearly touch at the top of the head, while females have slightly smaller eyes with a distinct gap between them.

Habits and Lifestyle

Black Horse Flies are creatures of habit, following predictable patterns that have served them well for millennia. These diurnal hunters are most active during the warmest parts of summer days, typically emerging when temperatures climb above 25°C (77°F). They possess an almost supernatural ability to detect carbon dioxide, body heat, and movement from distances exceeding 100 meters.

Notable behavior: Only female Black Horse Flies bite, requiring protein-rich blood meals for egg development, while males content themselves with nectar and plant juices.

Their hunting strategy combines patience with lightning-fast reflexes. Females often perch motionlessly on vegetation near trails, water sources, or areas frequented by large mammals, waiting for the perfect opportunity to strike. When a suitable host approaches, they launch themselves with remarkable speed and precision, their flight creating an unmistakable droning sound that can send even large animals into defensive mode.

Despite their fearsome reputation, these flies play crucial ecological roles beyond their blood-feeding habits. Males serve as important pollinators, visiting flowers for nectar and inadvertently transferring pollen between plants. Both sexes contribute to nutrient cycling in their ecosystems, and they serve as food sources for various bird species, spiders, and other predatory insects.

Distribution

The Black Horse Fly claims an impressive territory across much of North America, with populations thriving from southern Canada down to the Gulf Coast states. Their range extends from the Atlantic seaboard westward to the Great Plains, with particularly robust populations concentrated in the southeastern United States where warm, humid conditions provide ideal breeding environments.

These adaptable insects show remarkable habitat flexibility, colonizing diverse environments from coastal marshlands to inland forests, suburban parks to agricultural areas. They demonstrate a strong preference for locations near water sources—streams, ponds, wetlands, and even temporary pools created by summer rains. The proximity to water serves dual purposes: providing breeding sites for their aquatic larvae and attracting the mammals they depend upon for blood meals.

Habitat preferences include:

- Deciduous and mixed forests with clearings

- Wetland edges and riparian zones

- Suburban areas with adequate vegetation

- Agricultural landscapes with livestock

- Coastal plains and marshy regions

Diet and Nutrition

The feeding habits of Black Horse Flies reveal a fascinating tale of sexual specialization and ecological adaptation. Adult males lead relatively peaceful lives, sustaining themselves entirely on plant-based nutrition—sipping nectar from flowers, consuming tree sap, and feeding on other sugary plant secretions. Their role as inadvertent pollinators makes them valuable contributors to plant reproduction cycles.

Females, however, transform into formidable predators when reproductive needs arise. Their blood-feeding apparatus represents millions of years of evolutionary refinement: razor-sharp mandibles slice through skin while specialized pumping mechanisms extract blood with remarkable efficiency. A single feeding session can yield up to 200 milligrams of blood—nearly equivalent to the fly’s own body weight.

Preferred hosts include:

- Large mammals (horses, cattle, deer)

- Humans and domestic animals

- Occasionally birds and reptiles

- Any warm-blooded creature of sufficient size

The timing of blood meals coincides precisely with reproductive cycles. Females typically require 2-3 blood meals to develop a full complement of eggs, with feeding sessions spaced several days apart. Between blood meals, they may supplement their diet with nectar and plant juices, maintaining energy reserves for their demanding lifestyle.

Mating Habits

The reproductive cycle of Black Horse Flies unfolds as a complex dance of aerial acrobatics, territorial disputes, and precise timing. Mating season peaks during the hottest months of summer, typically from June through August, when environmental conditions optimize both adult activity and larval development prospects.

Males establish territories around potential breeding sites, engaging in spectacular aerial battles with rivals. These contests involve high-speed chases, aggressive buzzing displays, and physical confrontations that can last for hours. Successful males claim prime real estate near water sources where females will eventually deposit their eggs.

Courtship rituals are surprisingly brief but intense. Males intercept females during their host-seeking flights, engaging in rapid aerial pursuits that test both participants’ flying abilities. Successful mating occurs on vegetation or other surfaces, lasting only a few minutes before the pair separates.

Reproductive timeline:

- Mating: Mid to late summer

- Egg-laying: 3-7 days after blood meal

- Larval development: 1-2 years in aquatic environments

- Pupation: Spring emergence timing

- Adult lifespan: 30-60 days

Females deposit their eggs in distinctive masses on vegetation overhanging water or moist soil. Each egg mass contains 100-800 individual eggs, carefully positioned to ensure larvae drop directly into suitable aquatic habitats upon hatching. The larvae, known as “water tigers,” spend 1-2 years developing in muddy substrates, feeding on organic matter and small invertebrates.

Population and Conservation

Black Horse Flies currently maintain stable populations across their range, with no immediate conservation concerns threatening their survival. Their adaptability to various habitats and opportunistic feeding strategies have allowed them to persist even as landscapes change around them. Population trends remain largely unknown due to limited systematic monitoring, but observational data suggests healthy numbers in most regions.

However, certain environmental pressures could impact future populations. Wetland destruction poses the most significant threat, as these habitats provide essential breeding sites for larval development. Agricultural intensification, urban development, and climate change may alter the delicate balance of conditions these flies require for successful reproduction.

Conservation considerations:

- Wetland preservation critical for breeding success

- Pesticide use may impact adult and larval stages

- Climate change could shift distribution patterns

- Habitat fragmentation affects population connectivity

Interestingly, their role as disease vectors has led to extensive research into population control methods, creating an unusual conservation paradox. While public health concerns drive efforts to reduce their numbers in some areas, their ecological importance as pollinators and food web components argues for balanced management approaches that consider their broader environmental contributions.

Fun Facts

• Speed demons: Black Horse Flies can reach flight speeds of up to 25 mph, making them among the fastest flying insects in North America

• Ancient lineage: Fossil evidence suggests horse flies have existed virtually unchanged for over 100 million years, making them contemporary with dinosaurs

• Precision pilots: Their compound eyes contain up to 10,000 individual lenses, providing nearly 360-degree vision and exceptional motion detection

• Weather predictors: These flies are so sensitive to atmospheric pressure changes that their activity levels can predict approaching storms hours in advance

• Size matters: Larger individuals can bite through lightweight clothing, and their bite force is strong enough to penetrate thick animal hide

• Aquatic childhood: Their larvae are fierce underwater predators, capable of taking down prey much larger than themselves using powerful mandibles

• Temperature dependent: They become completely inactive when temperatures drop below 15°C (59°F), essentially hibernating until conditions improve

References

• Teskey, H.J. (1990). The Horse Flies and Deer Flies of Canada and Alaska. Agriculture Canada Research Branch.

• Pechuman, L.L., Webb, D.W., & Teskey, H.J. (1). The Diptera, or true flies, of Illinois I. Tabanidae. Illinois Natural History Survey Bulletin, 33(1), 1-122.

• Burger, J.F. (1995). Catalogue of Tabanidae (Diptera) of North America north of Mexico. International Contributions on Entomology, 1(1), 1-100.

• Krinsky, W.L. (1976). Animal disease agents transmitted by horse flies and deer flies (Diptera: Tabanidae). Journal of Medical Entomology, 13(3), 225-275.

• Chvála, M., Lyneborg, L., & Moucha, J. (1972). The Horse Flies of Europe (Diptera, Tabanidae). Entomological Society of Copenhagen.