Scruparia Chelata

Scruparia chelata

| Kingdom | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Phylum | Bryozoa |

| Class | Gymnolaemata |

| Order | Cheilostomatida |

| Family | Scrupariidae |

| Genus | Scruparia |

| Species | Scruparia chelata |

Key metrics will appear once data is available.

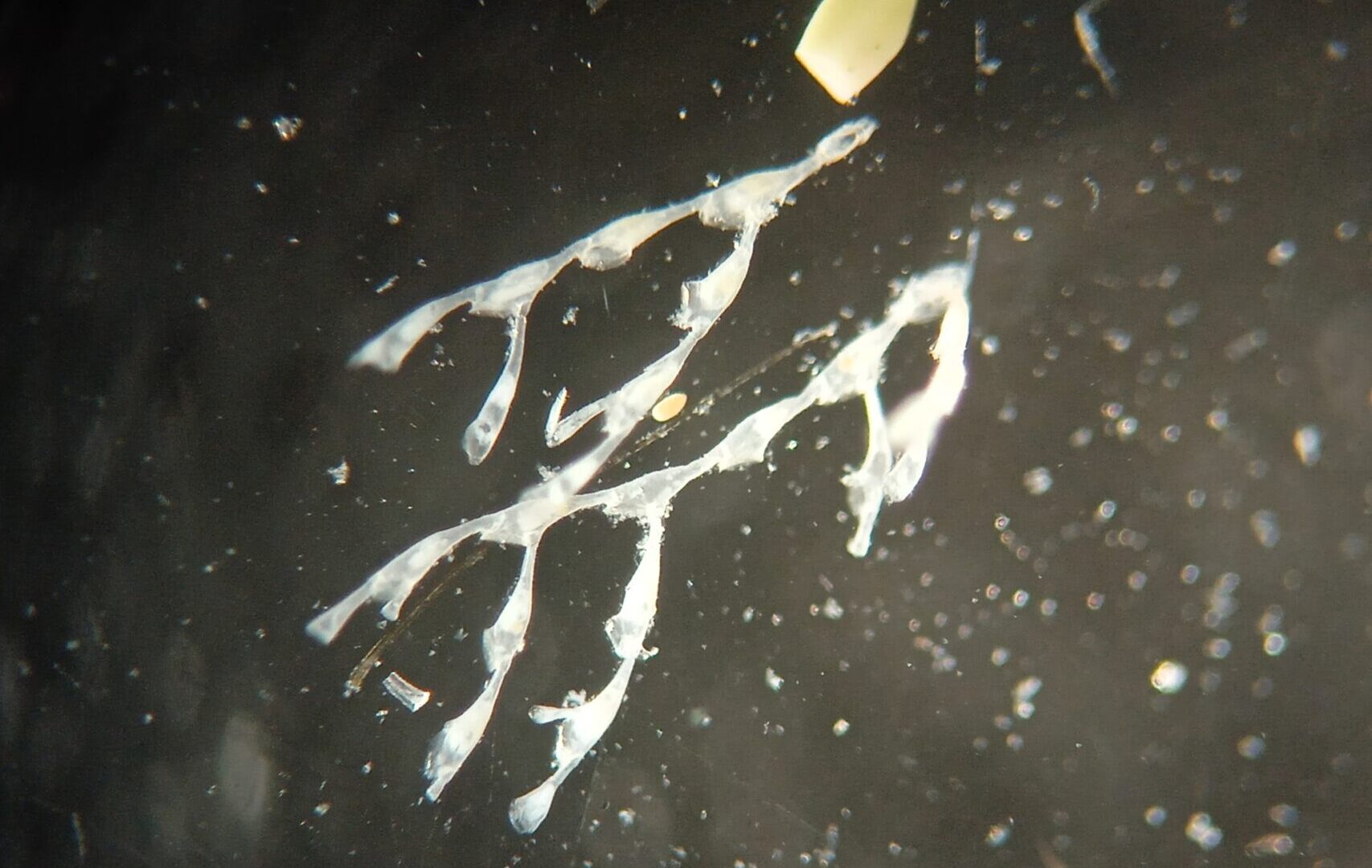

Scruparia chelata is a tiny marvel of the marine world—a colonial bryozoan that transforms invisible ecosystems into intricate living architectures. Found clinging to rocky shores, algae, and shells across the temperate Atlantic and Mediterranean waters, this delicate creature demonstrates how even the smallest organisms can build something extraordinary through cooperation.

Identification and Appearance

Scruparia chelata is a cheilostome bryozoan, meaning it belongs to the most diverse order of bryozoans alive today. Like all bryozoans, it is fundamentally a colonial animal—not a single organism, but a living city of interconnected zooids (individual animals). Each zooid is microscopic, typically less than a millimeter in length, yet together they form visible colonies that encrust or creep across hard surfaces.

The species is characterized by its distinctive creeping habit. Kenozooids form creeping stolons, which are specialized connecting tubes that allow the colony to spread horizontally across its substrate like a living vine. This growth pattern gives Scruparia chelata a delicate, branching appearance quite unlike the robust, sheet-like encrusting bryozoans of other species. The individual zooids possess mineralized exoskeletons that protect their soft bodies, with each zooid sitting within its own calcified chamber.

What makes identification distinctive is the species’ characteristic form: colonies typically grow in an open, spreading pattern rather than densely packed. The name “chelata” refers to claw-like structures, reflecting the appearance of the species’ specialized zooids. Cheilostome bryozoans have mineralized exoskeletons and form single-layered sheets which encrust over surfaces, and some colonies can creep very slowly by using spiny defensive zooids as legs.

Habits and Lifestyle

Scruparia chelata is distributed throughout western Europe and the Mediterranean. It can be found around the coasts of England, Wales and Ireland, and rarely in Scotland. The species is sessile and colonial, meaning individual zooids remain permanently attached to their chosen substrate. Once a larva settles and metamorphoses into the first zooid, it begins budding to create new zooids, which then bud to create more, rapidly building the colony through asexual reproduction.

The colony’s lifestyle revolves around filter-feeding. Bryozoans use a ring of cilia-lined tentacles, called a lophophore, which these species use to generate currents that assist in feeding on diatoms and other planktonic organisms. Each zooid extends its delicate crown of tentacles into the water column, creating microscopic currents that draw in food particles. When threatened or when water conditions become unfavorable, the zooids retract completely into their protective chambers.

Scruparia chelata is observed at different depths (5–25 m) on various substrates, both as detached specimens and attached to other organisms. The species shows remarkable flexibility in its habitat preferences, colonizing everything from living algae and hydroids to artificial structures and shipwrecks. This adaptability has allowed it to thrive in temperate waters despite being relatively uncommon in some regions.

Distribution

Scruparia chelata is distributed throughout western Europe and the Mediterranean. GBIF records document its presence across a wide geographic range spanning from Australia to Scandinavia. The species shows a strong preference for temperate waters, with the highest concentration of observations in the British Isles, Netherlands, France, and surrounding coastal areas.

The species colonises various substrates including algae, hydroids, stones and shells from the lower shores down to shallow depths. This substrate flexibility explains its broad distribution pattern. The species appears particularly abundant in areas with strong tidal currents and rocky outcrops, where hard surfaces provide ideal settlement sites and water movement delivers abundant plankton.

Diet and Nutrition

As a bryozoan, Scruparia chelata is a dedicated filter-feeder, extracting microscopic food from the surrounding water. The species relies entirely on its lophophore—the magnificent crown of tentacles that each zooid extends into the water. These tentacles are lined with cilia, tiny hair-like structures that beat in coordinated patterns to generate feeding currents.

The diet consists primarily of:

- Diatoms (single-celled algae)

- Planktonic organisms and larval forms

- Organic detritus suspended in the water

- Bacterial particles

Feeding occurs continuously whenever water conditions permit and the zooid is extended. The lophophore captures particles and directs them toward the mouth, which sits at the center of the tentacle crown. Their gut is U-shaped, with the mouth inside the crown of tentacles and the anus outside it. This efficient design allows waste to be expelled away from the feeding apparatus.

Mating Habits

The reproductive strategy of Scruparia chelata is complex and multifaceted, reflecting the sophistication of colonial life. The species employs both sexual and asexual reproduction, giving it tremendous flexibility in colonizing new environments and maintaining established populations.

Asexual reproduction through budding is the primary means of colony growth. All colonies start with one original zooid, around which all other zooids arrange themselves. New zooids bud from existing zooids, inheriting their genetic material and creating genetically identical clones. This allows a single successful larval settlement to rapidly establish a thriving colony.

Sexual reproduction occurs within the colony itself. Although those of many marine species function first as males and then as females, their colonies always contain a combination of zooids that are in their male and female stages. Specialized reproductive zooids within the colony produce eggs and sperm. It is possible that androzooids are used to exchange sperm between colonies when two mobile colonies or bryozoan-encrusted hermit crabs happen to encounter one another. The fertilized eggs develop into larvae that eventually settle on new substrates, dispersing the species across vast distances through ocean currents.

Population and Conservation

While comprehensive population data for Scruparia chelata remains limited, the species appears stable across its range. GBIF records document 742 total occurrences, with observations concentrated in European waters but also extending to Australia and other regions. Beached specimens, most likely originating from the English Channel, are common, though the species itself is considered relatively uncommon in some areas like the southern North Sea.

The species faces no immediate conservation threats and has not been formally assessed by the IUCN. However, like all marine organisms, Scruparia chelata is potentially vulnerable to broader threats affecting coastal ecosystems. Climate change, ocean acidification, and habitat degradation could impact the hard substrates and water quality this species requires. The species’ ability to colonize artificial structures like shipwrecks and gas platforms demonstrates its resilience and capacity to adapt to human-modified environments.

Fun Facts

-

Microscopic architects: While each individual zooid measures less than a millimeter, colonies can spread across several centimeters or more, creating visible structures from invisibly small building blocks

-

Creeping colonies: Unlike many bryozoans that form static encrusting sheets, Scruparia chelata slowly creeps across surfaces using specialized zooids as legs, allowing it to seek out better feeding locations

-

Ancient lineage: The genus Scruparia was formally described by Linnaeus in 1758, making this species among the earliest scientifically documented bryozoans

-

Dual reproduction: The species combines the speed of asexual budding with the genetic diversity of sexual reproduction, giving it evolutionary flexibility

-

Microscopic filter: Each zooid’s lophophore contains hundreds of cilia working in perfect synchronization to create feeding currents and capture particles invisible to the naked eye

-

Widespread hitchhiker: The species readily colonizes artificial structures and can be transported on ships, making it an accidental global traveler in maritime ecosystems

-

Hermaphroditic colonies: Individual zooids change sex during their lifetime, but colonies always maintain a balance of male and female zooids for successful reproduction

References

-

Hayward, P.J. & Ryland, J.S. (1990). The marine fauna of the British Isles and North-West Europe: 1. Introduction and protozoans to arthropods. Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK.

-

Bock, P. (2025). World List of Bryozoa. Scruparia chelata (Linnaeus, 1758). Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species.

-

De Blauwe, H. (2009). Bryozoa from the Belgian Continental Shelf and adjacent areas. Belgian Biodiversity Platform.

-

Animal Diversity Web. (2023). Bryozoa (moss animals). University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.